Quantum physics is often associated with a small circle of legendary male scientists, especially during its early development a century ago. Yet the record is full of women whose work shaped the foundations of the field in ways that remained uncredited for decades.

Their stories reveal how quantum science grew through routine experiments, meticulous calculations, and persistent labor carried out far from the spotlight.

Women Pioneers Behind Quantum Physics

During the 1960s, the large research initiative called Sources for History of Quantum Physics (SHQP) set out to document the origins of the field. Out of more than 100 interviews with early quantum researchers, only two included women. That underrepresentation might appear predictable, but the deeper historical record tells a richer story.

“Women in the History of Quantum Physics” highlights the contributions of female scientists active from the 1920s onward. The book presents 14 rigorously researched chapters, highlighting contributions made alongside prominent figures such as Niels Bohr, Wolfgang Pauli, and Paul Dirac. Despite the depth of their influence, many of these women remained absent from mainstream accounts of quantum theory.

Daniela Monaldi of York University in Canada, one of the book’s editors, notes that she and her collaborators sought “better stories, more rounded stories, stories that neither invisibilise women nor make them hyper visible as singular, anomalies, exceptions, legends and so on.”

Key Figures Whose Work Shaped the Field

These scientists expanded quantum theory, strengthened experimental foundations, and quietly sustained progress through everyday research tasks.

Hertha Sponer

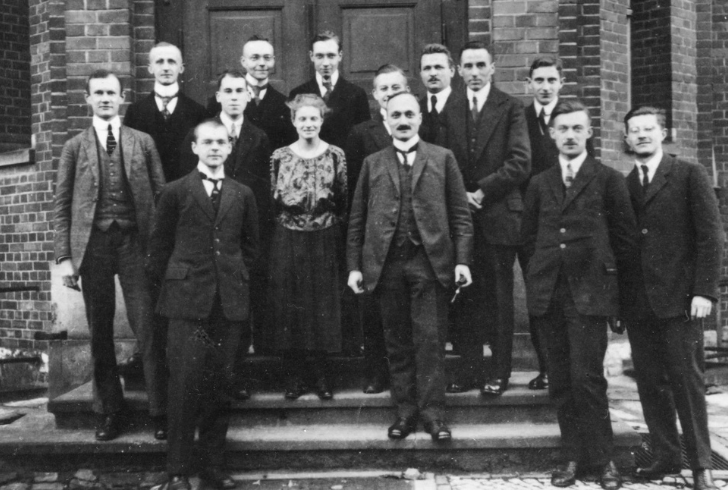

Instagram | aip.org | Sponer's molecular quantum behavior studies gave valuable support to Bohr's theories.

Her laboratory studies on molecular quantum behavior provided valuable tests of Bohr’s theories. A photograph from the University of Göttingen shows Sponer among colleagues who were establishing some of physics’ most influential ideas.

Williamina Fleming

Her stellar spectroscopy analysis supported evidence for Bohr’s quantum model of the helium atomic ion. By studying starlight patterns, she generated data that later confirmed central ideas about atomic structure.

Lucy Mensing

Mensing was one of the first to apply matrix mathematics to quantum problems. This work laid the groundwork for modern approaches used today in research on quantum spin and other core concepts.

Katharine Way

Way contributed heavily to nuclear physics and developed key databases and publications that became essential technical references across the field.

Carolyn Parker

Parker, the first African American woman to earn a postgraduate degree in physics, advanced spectroscopy research, and faced barriers under Jim Crow laws that limited her full participation in scientific communities.

Grete Hermann and Chien-Shiung Wu

Hermann shaped philosophical and mathematical discussions around quantum theory, while Wu conducted pioneering experiments in nuclear physics. Her early work with quantum entanglement—long before it became a driving force in modern quantum technologies—remains one of the field’s overlooked achievements.

What Their Work Reveals

A running theme across these profiles is the everyday nature of their contributions. They published research, built laboratory equipment, trained military technicians during the 1940s, and supported government research programs. Their careers were shaped by ordinary tasks that quietly advanced the field of quantum physics step by step.

The book shows how theoretical ideas from Bohr, Einstein, or Schrödinger required validation through experiments, measurements, and repeated trials—roles often assigned to women. Their positions as laboratory workers, experimentalists, or teachers made their contributions essential, though not always acknowledged.

Many of these scientists also taught students who went on to influence physics. Sponer and Hendrika Johanna van Leeuwen, who demonstrated that magnetism is inherently quantum in origin, helped educate future generations who continued expanding the field.

Structural Barriers That Limited Recognition

Social norms and academic systems shaped these women’s careers in ways that delayed or erased recognition.

1. Many married fellow physicists, and nepotism rules penalized them more than their husbands.

2. Hertha Sponer, for example, was repeatedly mislabeled as her husband’s student despite evidence showing otherwise.

3. Freda Friedman Salzman lost a research position due to nepotism policies, while her husband remained employed in the same department.

These patterns repeated across the book and reflect how institutional structures routinely undermined the visibility of women in physics.

Intersectional identities also influenced their careers. Wu’s experience as an immigrant from China affected her academic path, while Parker confronted racial discrimination that restricted opportunities and access to scientific networks.

A Timely Reflection on the Field

Instagram | nnsanews | Carolyn Parker, the first Black woman with a physics master's, faced Jim Crow research limits.

The United Nations designated 2025 as the International Year of Quantum Science and Technology, bringing attention to the field’s past and future. The moment also coincides with challenges in the United States, including reduced funding for research programs and political pushback against diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives.

Monaldi notes that diversity “means uniting forces that come from different standpoints to solve common problems,” especially as global challenges demand broad scientific cooperation.

The stories collected in “Women in the History of Quantum Physics” reinforce that major scientific progress rarely comes from a few extraordinary individuals. Quantum physics grew through the labor of many people—women included—whose expertise and routine work kept research moving forward.

A Lasting Impact on Quantum Science

The women who shaped quantum physics reveal a field built through persistence, experimentation, and shared effort. Their contributions—spanning spectroscopy, nuclear research, matrix mathematics, and teaching—formed part of the foundation that allowed quantum science to flourish.

Revisiting their work expands historical understanding and underscores the importance of recognizing every contributor who helped assemble one of the most influential areas of modern science.